SLIP INSIDE

THIS HOUSE *Some excerpts from the following are taken from Brew Brewster and Frank Broughton’s excellent and seminal 2022 text “Last Night A DJ…” White Rabbit Books.

Some of the most meaningful moments in my life have been moments on a dancefloor or behind a pair of decks, moments beyond something, of non-representational experience. I’m not a musician by training or by any means, but I have been studying its structure and theory autodidactically since falling in love with electronic music in my early teens. Over the years and during the later part of my candidacy, I have come to realise that DJ’s can be those of us who study and have careers – but somehow ended up part of an extended after-dark family. My night-time family have always allowed me to drop the super-egoic vigilance which I’d come to wrap around myself, surrendering egoic agency & mastery and allow myself to open up to the otherness of a crowd and a good sound system.

Dancefloors have the potential to unite people through sound, in a way that governments and religions try to separate us. In our day to day lives our bodies are alienated, overridden and over-coded by language. Music isn’t a language as such, as it doesn’t have an accepted narrative structure, but it could be considered a language of intensity and feeling perhaps. Akin to psychoanalysis, good electronic music is a language of intimacy, texture and relationality and offers a dialogue of feeling. Whereas the late capitalistism we endure and try and make a life for ourselves in very much A-Relational.

We are overwhelmed and bombarded in our day to day lives noise and the problem these days isn’t that I might like or not like what I hear, but that I may not be able to feel. That I may not be able to enter into a domain in which music can affect me in a meaningful way. A way in which, I can change my sense of where I am in my life, and of hope in a despairing socio-political epoch.

I’ve always been drawn to the imaginary and the after dark world of affectual soundscapes, a seeing of the shape in the fire, of ecstasy and dream like states. My cultural and social affiliations as a working-class kid have always found a home in the world of electronic music and over the years I have gravitated from the house music of Detroit, Chicago and New York to the more underground, weird and widdy styles of European house associated with Vilnius, Berlin, Paris, London, Manchester and Bristol. A leaving behind of American DJ egos and turf wars - in favour of a European ideological approach to harmony & melody. My favourite amulets so to speak, have become low slung, chuggy House records with emotional complexity and minimal, grubby, dubby Techno, with its deep rhythmic structure which hits right in the chest akin to a Roustangian hypnotic trancelike state. For me music offers the potential of an interlocutor, a line of flight, of escapism, connection and acceptance, and where I first experienced a real sense of belonging in this world.

When I play records, its about captivating people into a felt sense of otherness and movement. Dancing is a politic of the body and both DJ’ing and dancing are political acts. The cultures and communities that formed around the DJ booth have been vitally important for marginalised people. From the swing kids defying the Nazis, to the rebellious teenagers of hip hop, to the queer underground of the first disco clubs. DJ culture & more Avant Garde styles of electronic music have always created safe spaces and offered refuge, whether from bigotry and oppression or just from an older generation. A good DJ uses the power of music to suspend reality, a forgetting of your career struggles, the mortgage or increasing overdrafts, a rejecting the rules and responsibilities of the day light hours and a questioning of the values that make you wait for the bus to the office and perform a smile to your boss each morning. As you join a dancefloor you're forging an alliance, however briefly, with 10’s, hundreds, maybe thousands of people. Ultimately, dancing is collective action, an unspoken agreement to do something somatic together.

For millennials like myself, some historical context is important here…

In Chicago, as the seventies became the eighties, if you were black and gay your church may well have been Frankie Knuckles’ Warehouse; a three-story factory building in the city’s desolate west side industrial zone.

One day a week, from Saturday night to Sunday afternoon, a faithful crowd gathered at 206 North Jefferson, waiting on the stairway to enter on the top floor of the building and pay the democratically low $4 admission. The club held around 600, but as many as 2,000– mostly gay people of colour, and nearly all from marginalised communities– would pass through its doors during a good night. They dressed with elegance, but in clothes that declared a readiness to sweat.

Once in the club, some stayed in the seating area upstairs.

Others walked down to the basement for the free juice, water and other provisions.

Most people, however, headed straight to the dark, sweaty dancefloor in between.

Offering hope and salvation to those who had few other places to go, here you could forget your troubles and escape to a better place.

Like church, it promised freedom, and not even in the next life.

In this space Knuckles took his congregation on journeys of redemption and discovery.

For them there was no need for distraction: they came here for Frankie Knuckles’s records.

They came to the Warehouse to dance to House music.

For a long time the word ‘house’ referred not so much to a particular style of music, but to an attitude. If a song was ‘house’ it was music from a cool club, it was underground, it was something you’d never hear on the radio. In Chicago, the right club would be ‘house’, and if you went there, you’d be ‘house’ and so would your mates. Walking down Michigan Avenue, you would be able to tell who was ‘house’ and who wasn’t by what they were wearing. If their tape player was rocking the Gap Band, they were definitely not ‘house’, but if it was playing Loleatta Holloway or Eurythmics, they were, and you’d probably go over and talk to them. ‘House’ was a feeling, a rebellious musical taste, a way of declaring yourself in the know. Certainly, the word ‘house’ was used long before people started making what we would now call ‘house music’.

Over here in the UK, in 1987, change was in the air. Gorbachev's glasnost was starting to defrost the Cold War and Democracy movements were beginning to thrive across Eastern Europe. Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government, exhausted and exhausting, spluttered to another election victory, while the country was still in turmoil from industrial conflict. The stock market crash in October signalled a massive downturn in the economy and a collapse in the housing market, leaving many with mortgages higher than their homes were worth. Celebrating her third term with the callousness that would make it her last,

Thatcher claimed,

'There is no such thing as society.

There are individual men and women, and there are families.’

The implication was that to succeed you had to detach yourself from any collective spirit.

No U-turns, no sympathy and no soul.

The snobbery of London's club scene was also breeding opposition. Working-class casuals like DJ Terry Farley resented being forced to adopt the styles of the ruling St Martins art school cliques.

“To get into the clubs at night we would have to change the way we looked completely.

We couldn't go straight from the footy we had to go home and get changed.

It did piss us off. I knew as much, as they did about records, but I could only come in if I got changed!” Terry Farley

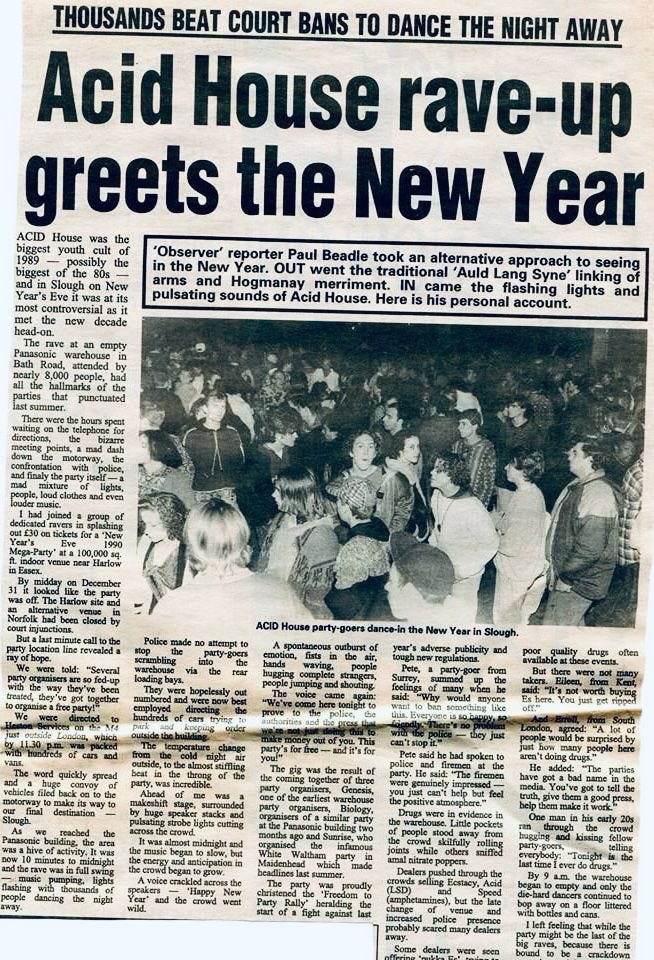

Farley went on to become a household name during this era, an era of Acid house, when Britain finally shook off the grey dust it had been wearing since the war. A nation built on conservatism, acceptance and duty started asking a few questions. Though there weren't many answers, working class Britian started to become a very different place. There'd been plenty of sunny moments before, but none as weirdly disruptively or creatively universal.

It was a moment in time, more than just partying for the sake of getting on the piss, it was cathartic. In the sixties you could tune in, turn off and drop out, but only if you were a hip photographer or if daddy kept up the rent on the Kings Road flat.

The 90’s became a voyage of discovery, which was opened up to nearly everyone.

Gas fitters became record producers, market traders launched fashion labels, cooks started magazines; and all over the UK the country’s kids stopped wanting to grow into cool, successful, Armani-suited adults, and settled gleefully for a more kindred sprit.

At the tail end of a decade which had been about greed and shoulder-pads and black marble office blocks, along came a youth culture of smiley faces, of togetherness and talking bollocks.

The night your mate danced like a tree.

The night the whole club thought they'd been up in a space-ship.

The night you met all the people who are now your best friends.

The night everyone's name was Doug.

The night you gave away your Gucci boots 'cos they were annoying you.

The night it was all about being underwater.

The night you thought you'd lost everybody but they were just hiding.

The night you danced in a car park.

The night you gave up trying to get promoted and decided to make clothes instead.

The night we stroked people's hair for drinks.

The night you talked about losing your dad and cried and finally understood.

The night you twisted your ankle but didn't tell anyone in case they made you go home.

The night everyone ended up in Chester - speaking in Scottish accents.

Fun. Suddenly it was important.

Like puppies tumbling around the garden, people found the best way to learn about our world was to play. It taught us a lot of what we might have missed otherwise - most importantly that while the things that make people different are pretty obvious, the things we all have in common aren't that hard to find either.

Acid house was nothing less than a defining era of British social history, a cultural revolution. For me, you can’t fully understand today's Britain without knowing the changes it brought. As Thatcher swept away the post-war community ideal and replaced it with the free market and its cult of selfish individualism, here was a youth movement that proposed the opposite. Here was music that meant little, unless you shared it.

Strictly speaking, 'acid house' refers to a few records made using the distinctive squelching of a distressed Roland 303, the productions of the Chicago and Detroit kids who were looking to the future, rather than merely reheating disco. After Phuture's 'Acid Tracks' set the mould, a bleeping flurry of similar records followed, both imported and UK-made.

However, with most listeners ignorant of any distinctions, 'acid house' was soon shorthand for house, techno and even Balearic tunes as a whole. So while acid house began as a specific musical subgenre, in Britain it became a blanket name for this new electronic dance music, and then for the whole culture of the early 90’s.

On September 23 1991 Scottish band Primal Scream released Screamadelica, their third studio album. The album marked a significant departure from the band's early indie influences, drawing inspiration from the blossoming acid house scene. Much of the album's magic comes from its production by pioneering DJ and producer Andrew Weatherall. Weatherall’s wizardry and Midas touch of adding samples, loops and creating an influential mix of indie, house and rave helped the record win the first ever Mercury Music Prize in 92 and become one of the most celebrated albums of the 90s.

In our house, this amulet is a firm favourite and a defining track from this era.

Bobby Gillespie begins the track…

Finer worlds that you uncover

Plant the path you want to roam

Live where your heart can be given

And your life starts to unfold

Rest in power Andrew.

“Fail we may, sail we must”