Mixtape

By JH

Description of the amulet:

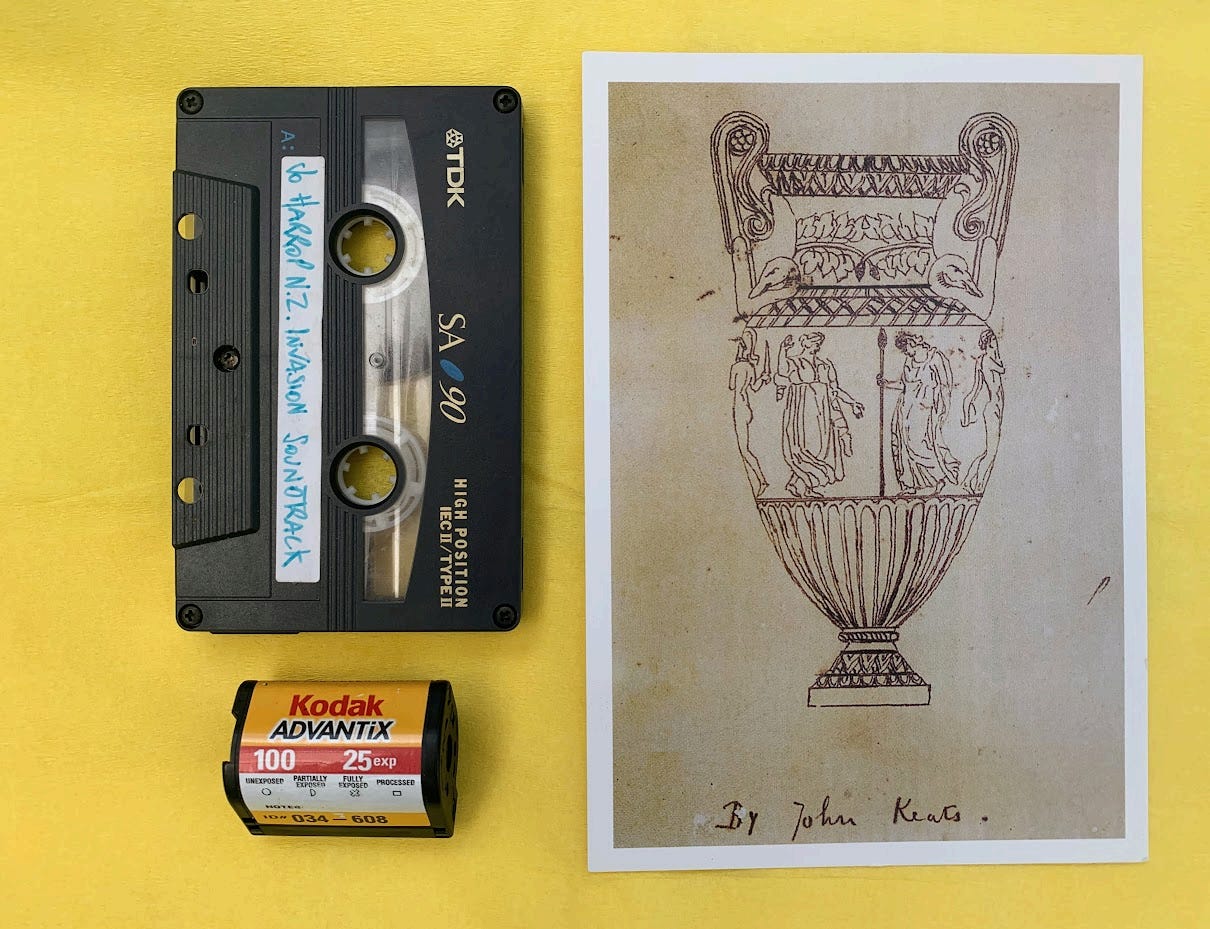

A 90 minute audio cassette dating from 2004.

The accompanying objects are a postcard showing John Keats’ drawing of the Sosibios Vase, and an undeveloped roll of camera film also dating from 2004.

Twenty one years ago, on a journey to the other side of the world, I played and replayed this mixtape. The tape was given to me as a parting gift from the one who compiled it, and I listened closely to the choice of songs, the words, the sound and texture of the music, reaching for their meaning as communication from an absent other. A handwritten list of songs was originally tucked into the cassette case but has been lost over time. The tape has not been played for twenty years, and memory of the songs that are on the tape remains partial.

Some fragments of text to speak to the silence of the object:

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear'd,

Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone:

Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave

Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal

John Keats, ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’

[The potter] creates the vase with his hand around this emptiness

Lacan, The Ethics of Psychoanalysis

This third fragment was written for me by RO (mixer of the mix tape)

There’s a million possibilities [of the songs that were chosen] and if I made you a tape today it might contain the same songs but they’d have different meanings. You’ve got an inanimate object but it changes shape. I’ve got something very similar: an undeveloped roll of film - do you remember? You took some photos but we never developed them. I’ve got an idea of what’s on it but can never know for certain. The film has probably deteriorated past the point of saving by now. But it doesn’t matter. I can see those photos anytime. I’d probably never look at the pictures if I had them anyway, just like you’d probably never listen to those old songs. But that’s what makes the pictures so vivid. It’s memory that makes those songs soar. It’s the almost. The nearly. You can hold these things in your hand but they’re still out of reach. They’re full of meaning and magic.

RO, ‘Cherished Memorex - songs you can’t hear’

And my own fragments of thought:

Keats in his ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ describes the scenes carved upon a marble vase, an urn. These are scenes of lovers, of musicians playing pipes, of a heifer being taken to be sacrificed. Keats describes these carvings and the figures as fixed in time, their music, their “unheard melodies'' will always be playing, and the dancers will always be dancing, the trees will never shed their leaves, the lovers will always desire, but never have the kiss they move towards, the spring will never end. They are held in time and silence.

If Keats were on the couch, clutching in defence his Grecian urn with it’s scenes of stilled time and silent beauty, we might want to hear more about his ambivalent wish for, and horror of, something held fixed and untouched in time, to invite him to speak the unheard melodies he holds to be sweeter in their silence, to bring into question the rich distinction between ‘protection’ and ‘defence’ when thinking of an amulet. Keats looks upon the surface of the vase, its carved forms, its myths and scenes of sacrifice and music. He muses upon, but does not look within. There is much to distract us in these scenes, waylaid by the dancers, and lost in thought about the music they play, we step with them not into, but out of time. What Keats does not speak about is the vase as vase, as an empty vessel, as shaped around a void.

Keats wrote eloquently on the unheard of the scenes on the surface of the urn, but what of this unnamable void around which these scenes circulate? The poet would then be coming up against the edge of language, where words fail. He too neatly arrives at his famous closing lines “Beauty is truth, truth beauty, - that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know” and seals the poem and seals the urn with these closing words that have frustrated many. T. S. Elliot, who wrote in his own poetry of our propensity to be ‘distracted from distraction by distraction’, called these final lines a blemish to the poem. These last lines are seductive but impossible to get inside, just as the poem itself never gives thought or expression to the void inside the vase, but dances around it in the heady mix of myth, and imagined melody, and scenes of dance and sacrifice. These last lines keep us on the surface, a turn to the positive and away from the negative space, speaking not of the unknown, but of what we know and what we need to know.

There are other truths here on which Keats is silent. Time may have been stilled in the narrative scenes carved upon it, but the vase itself has a history as an object of time and place, a history that was not stopped in time. Truth is not beauty, there is more we need to know. Keats saw the vase in Paris in 1816, the same year that he was equally enchanted by visits to view the Parthenon marbles in the British Museum. Collections enriched through colonial looting, institutions built with a Colonial mindset which can still be heard in disputes of ownership and repatriation today. The unheard melodies of the scenes upon the vase may well be sweeter than those that it lived through, first in its removal from its homeland to the royal collection of Louis XIV, then in its confiscation during the French Revolution to become part of the National museum of France.

A cassette taken to the other side of the world twenty one years ago. It sang and spoke and played. Keats’ ambivalent response to the silent urn mirrors my own uncertainty as to the status of the tape today. Is it performing now the mute work of containing and holding a time and a place? Is this pact of silence I have with the tape one of protection or defence? I could propose that this layering of new sounds and words onto the object is a way for it to play new heard melodies. But am I then, like Keats, being drawn too much into the imaginary realm of the stilled scenes and the unheard songs, a distraction from something more difficult, impossible even, to name at its centre.

The tape did not stop when it no longer played. Nor did the unknown begin with the loss of the playlist of songs and the tape’s descent into silence. Was I not also, or more so, faced with the unknown when the songs sang, when I listened and tried to grasp what another person was communicating in their choice and arrangement of music, with the want to know another and figure their desire? What I encountered instead was the unknown of ourselves to ourselves and to each other. What void does this cassette tape, or any object or amulet work to define? The unheard of the forgotten songs is not an unknown that is truly beyond our ability to grasp or think or speak, but by opening up thinking about what is unnameable, and as a negative space given form by the dialogue it has generated, where might it lead us? We can use such objects to protect and defend against the unknown, or we can take their poetry of absence as a way to question, not only what is unheard, but also what truths we might not want to know, what we thought could not be spoken.

When I give this tape the name of amulet it changes shape and keeps changing shape, it becomes and keeps becoming an object in time. Not one that holds 90 minutes of silenced sound, but one that has been held though 20 years of history. The story of this mixtape, its endurance in my life, and my care for it as an amulet of meaning and magic, speaks its own music and truth.